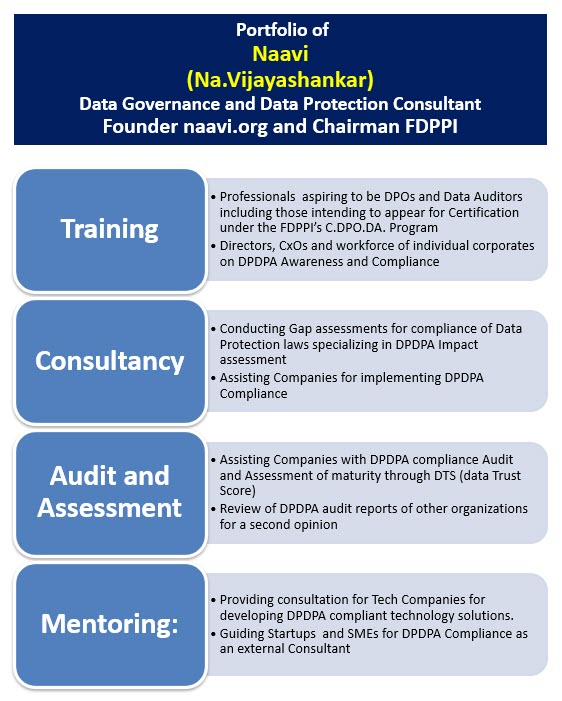

This is in continuation of my response to the question raised by a professional on why anybody should chose FDPPI Certification instead of other certifications available at a lesser cost.

Naavi’s views on the commoditization of ” CDPO” as a tag that can be acquired just by registering for an online webinar.

Being a “CDPO” does not end with only knowing DPDPA 2023. It should try to equip the professional the ability to take the responsibility of being a DPO.

We observe that there is a proliferation of “CDPO” courses to take advantage of the rush in demand for professionals to be “Certified as CDPO”.

While it is good that there are many organizations who are into the providing education related to Data Protection, just as it has happened in the ISO certification game, “CDPO” certificates have become a commodity on sale or close to being so.

This should stop.

If anybody can register themselves for a webinar and be called “Certified” DPO, it would dilute the quality of other DPOs who with years of experience and hours of effort try to understand the application of the law into the technical environment in a systematic manner.

There are three elements of being a good DPO. First they should understand the law. Second they should understand how technical architecture has to be re-built to meet the legal requirements. Third, there should be a handbook for guidance of how to meet the requirements.

Lastly, “Participation” in a program is necessary but not sufficient to consider a person “Certified”.

FDPPI therefore provides “participation Certificates” different from the final “Certificate” which is issued only after a successful completion of an examination. “Evaluation based certificates” are different from “Participation Certificates”, both of which have their values but Evaluation based certificates are distinctly superior to Participation certificates.

FDPPI does not end its Certification training with classes on DPDPA 2023 only but discusses the technical challenges and extends it with a “Framework” as a guideline. The “Framework of FDPPI” for DPDPA Compliance is DGPSI which is available as an open source framework both in “Lite” version as well as “Full Version” with an extension for AI Deployment.

At present there is no other training program that discusses a DPDPA Compliance framework along with the DPDPA law and Implementation challenges.

We want professionals who are aiming to acquire “Knowledge and Skills” donot fall into the trap of picking up “Webinar Participation Certificates” and call themselves “Certified”.

I hope organizations who recruit DPDPA Trained professionals distinguish the two kinds of certificates and ask “Where were you Certified and How?” before accepting any body as a “Certified DPO”.

FDPPI’s C.DPO.DA. program is conducted in offline and online modes from time to time. The next program is being conducted online on December 20 and 21. for which registrations are now open.

Fees for early birds upto 12th is Rs 25000/-. Subsequently it will be Rs 29500/- with GST.

It is a comprehensive program which covers the law, the technology challenges as well as the implementation framework. The 12 hour online session is supplemented with another 12 hours and 43 minutes of recorded videos which include GDPR coverage in detail. Reading material and recommended books make the kit of the “Certified” professional complete.

The C.DPO.DA. participants get 12 hours of CPE credit and a participation certificate which is different from the final certificate which is issued to those who pass a three hour online examination.

Yes..it is tough to be a C.DPO.DA. from FDPPI but we want “Certificates” to be earned.

All participants of the FDPPI course also get one year complimentary membership of FDPPI for continued interaction with likeminded professionals. This will enable the participants to continue to be under mentorship of FDPPI/Naavi when they have to implement their acquired knowledge in practice.

So, think before you chose how you are to be “Certified” as DPO.

I hope my friend who asked the question “Why FDPPI” is satisfied.

Any other comment is welcome.

Naavi

It is the desire of FDPPI/Naavi that all those who are associated with FDPPI during the last 7 years of its existence should consider themselves to be forming an eco-system to drive DPDPA compliance culture in the country.

It is the desire of FDPPI/Naavi that all those who are associated with FDPPI during the last 7 years of its existence should consider themselves to be forming an eco-system to drive DPDPA compliance culture in the country.