As the industry expects the “Draft Rules for DPDPA” to be released within the next fortnight, the draft of the draft rules released some time back selectively by MeitY to organizations like Meta and Google for their views provide us a glimpse of what the rules could be when it is finally released.

With the option given to MeitY to disown the publication, the draft of draft rules related to DPDPA is available for discussion at www.dpdpa.in/dpdpa_rules.

In the 20 rules and 7 schedules published here, rules 2 (definitions) 3, 4, 5, 10 and schedule I specifically relates to Notice, Consent and Consent Manager including verifiable consent for minors. A model consent artifact is also provided in schedule I.

In this connection, Data Fiduciaries need to focus on a few challenges highlighted below.

Firstly the Rules suggest that every consent shall carry the electronic signature of the data principal, the data fiduciary and the consent manager. Since the data principals may not have a digital certificate to enable such signature, and the onus of proof of consent is with the Data Fiduciary, the Data Fiduciaries need to make arrangements for the electronic signature like e-Sign.

While authentication of the consent is essential, provision should be made to use innovative but legally consistent methods to authenticate an electronic document without the use of electronic signature to reduce the cost incidence.

A positive aspect of the model consent artifact is an undertaking by the Data Fiduciary that the consent would be used only for the specified purpose. When this undertaking is also digitally signed, this constitutes a legal commitment.

The data fiduciaries need to ensure that they stand upto this commitment and introduce appropriate controls to ensure that the consent is automatically considered withdrawn as soon as the purpose expires and obtain fresh consent when the purpose is subsequently renewed. Otherwise they may be sued for “breach of Trust” under BNS 2023. (Refer Section 316 )

It is important to note that “Consent” is a document which has to be separately stored and may have to be retained for a period beyond the retention of personal data. In case of Consent Manager it may have to be retained for 7 years as per the draft of draft rules. Retention of consent for a data which itself is not retained is a vague concept and will lead to a dispute on what the consent is for. Hence the data fiduciary has to be meticulous to identify what data was part of a consent.

It is interesting to observe that the recognition that the “Consent” document is different from the data itself indicates that the ownership of the data lies with the data principal but the ownership of the consent lies with the Data Fiduciary and is not subject to the “Deletion” request from the data principal.

This supports our jurisprudential contention that “Data Ownership” of meta data lies with the platform and of transaction data lies jointly with the platform and the data principal.

It is doubtful how we can handle the issues such as when the data principal says “Consent is accepted but the data is erroneous and I did not give consent to this erroneous data”. This is another recipe for dark pattern usage.

The rules provide that the consent artifact is consistent with the DEPA framework provided by MeitY and every notice for consent has to be referred to the data principal and specific consent obtained. In such a scenario, the Data Principal is providing his signed consent and the role of the Consent Manager is only limited to the extent of forwarding the message to the data principal. This makes the role of Consent manager completely redundant.

There is a need to recognize the Consent Manager as similar to being a “Trustee” of a Data Principal and provide full rights to represent him for giving, modifying and withdrawing consent with an ability to assess the request for information against the purpose and challenge the Data Fiduciary on behalf of the data principal, monitor the use and demand deletion of the consent, the purpose of introducing the concept of Consent Manager is defeated.

It is at present not clear if the use of a “Consent manager” service is at the option of the data fiduciary or at the option of the data principal. This has to be clarified but requires the consent managers to be first set up and therefore a time line has to be indicated for adoption.

If the consent manager system is delinked from the current DEPA concept, the issues of digital signing, language issues, dark patterns in obtaining consent can be effectively handled. But this requires a complete re-thinking of the concept of Consent Manager by MeitY.

Further it is suggested that the Notice and Consent are structured in such a manner that “Purpose wise Collection of personal data elements” is enabled under one single consent. It would be more practical for the data fiduciaries to design different consent artifacts for different purposes rather than create one consent artifact for multiple purposes under one consent ID and dividing it into multiple permissions. The possibility of mis-application of permissions is very high in this system.

The model consent artifact is misleading and does not address the requirements properly. Hence it is preferable to delete the schedule I .

It is for this purpose that DGPSI recommends that Notice and Consent should be linked to different processes and managed process wise. In this system there would be multiple consents from a single data principal to a data fiduciary.

The next important challenge is to obtain the consent renewal for legacy consents. Since the rule in this regard is applicable to all previous data for which “Consent has already been obtained”, it does not apply to such cases where the data fiduciary may not be able to prove the existence of past consent. Hence all such data needs to be discarded.

It is therefore essential for data fiduciaries to use a “Legitimate Use” basis and current legal obligations to continue to hold the data in their archive while removing it from the processing activity.

Provision should be made for release of notice through public notices and continue secure archival for a reasonable time before deletion. Since “Deletion” could result in unintentional violation of other laws it is recommended that the Government should notify a “National Archival of Personal Data” and after a limitation period in which the personal data is securely archived at the Data Fiduciary, it may be transferred to the new National Archival created.

The next problem arises regarding the rule which requires “Verifiable Consent” for minors. Most Data Fiduciaries are considering that this would apply only if their services are directed to minors. However Section 9 of DPDPA applies to Minors and Disabled persons and the first verification required is whether the data principal is a minor or disabled person or not. This means that in every consent there has to be a “Due Diligence Verification” that the person is not a minor or mentally disabled person. Then there has to be another verification of who is the guardian. A third verification is required when the person attains majority when the now turned adult has to be identified and consent switched back to him.

In case of Minors, it may be possible to use the “Age Pass” created by checking with UIDAI but the identification of disabled persons requires a new judicial process to be introduced.

Yet another challenge is to understand the concept of “Legitimate Use” for processing personal data.

It must be remembered that a Data Fiduciary is by nature a “Trustee” and not a “Manger” of data appointed by the Data Principal. Hence irrespective of the consent, a Data Fiduciary should independently evaluate the legal basis and take a view in the interest of the “Data Principal”.

Legitimate use can be applied by non-Government agencies when the data principal has provided the data “Voluntarily” or when it is required for employment purpose or obligation of any law or for medical emergency.

There is no specific manner in which its “Voluntary” action of the data principal can be effectively recognized. Every collection of personal data is for a purpose and the purpose is to deliver a “Consideration”. Hence the question of providing any data “Voluntarily” does not arise. If this is not clarified, this will be a provision which is grossly abused. The illustrations provided are irrelevant. The provision essentially boils down to an automatic “Opt-in” without any indication of a positive intention.

In the illustration provided in the Act, (pharmacy), the primary service of the pharmacy is receiving the money without service and the augmented service is receipt of money with acknowledgement. Hence the Data Principal is actually opting for the augmented service for which the additional data is being provided and not “Voluntarily”. Similarly, in the second illustration of the real estate broker, the broker provides a service to receive the additional data which the data principal has to share .

These are purpose oriented collections and donot have a “Voluntary” nature. Even the “Publicly made available personal data” provision is potentially liable to be misused and the rules fail to provide the required clarifications.

Use of personal data for legal obligation is a genuine requirement but the Data Fiduciary needs to have a policy support and case to case authorization from the legal department before discarding the consent mechanism for establishing legal basis. DGPSI provides for this.

The legitimate use in employment circumstances relate to safeguarding the data fiduciary and is a genuine need. However the data fiduciary needs to understand that there is a relationship in employment which starts before the person is onboarded and after he is terminated. These have to be structured into the controls besides establishing on a case to case basis how the processing safeguards the data fiduciary. DGPSI provides for this.

In summary, the “Consent” is a challenge and unless an organization understands the full implications of how to take a valid consent, retain it for reference and retrieve it when required and how to use the consent manager service and whether the use of consent manager is optional etc.

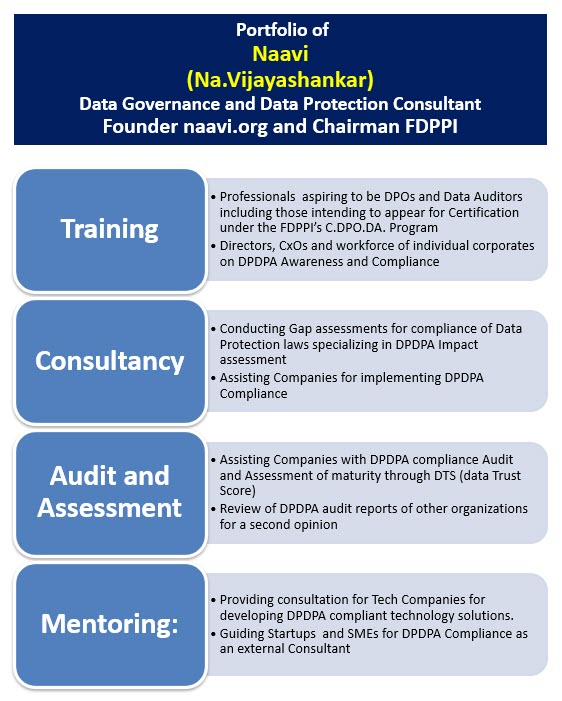

Naavi