Information Technology Act 2000 (ITA 2000) has been in existence since 17th October 2000 and in the amendment of 2008, effective from 27th October 2009, Section 79 was amended and subsequently “Intermediary rules 2011” were notified under the section with effect from 11th April 2011. On 25th February 2021, the Government of India announced a revision of which we may refer to as the “Intermediary Rules 2021”.

It was a general observation of the society that “Fake News” proliferated in the digital media and many of these digital media houses were owned and controlled by foreign business interests. There were also individuals who were using the privilege of easy publishing without any accountability using You Tube and OTT platforms. “Yellow Journalism” was spreading like wild fire in the digital media and the Government thought it was necessary to regulate this media just like the Press Council tries to discipline the print media or the Cable TV act tries to impose some responsibilities on the TV medium.

During the farmer’s agitation, it was clear that paid celebrity tweeters from abroad were commenting on the Indian developments without knowing the facts. These motivated celebrity tweeters and “Fake Journalists” were teaming up with “Foreign Agents” to spread political messages through the digital media with a specific objective of embarrassing the Government.

It was natural that many of the activists considered that the Intermediary Guidelines 2021 was an opportunity with which Government could be bashed in the Indian Courts. Hence several cases were registered in the High Courts as PIL or in the name of journalists. Though the Government of India has requested for the transfer of these cases to the Supreme Court, High Courts in their eagerness to stamp their views have been releasing their orders as if it is a matter of national emergency instead of letting the Supreme Court take over the cases. Two such orders have already been released one by the Madras High Court and the other by the Mumbai High Court staying some of the provisions of the notification of February 25th.

It is now well known that media of today is no longer the “Fourth Pillar of democracy” and is only a commercial arm of business. They have their own agenda including over turning elected establishments. We know that one of the prominent US media house even released advertisement to recruit reporters based in Delhi with a specification that the Journalist should report with a specified bias against the current Government.

The knowledge of these developments was before the Courts and there was a need to appreciate that it was a legitimate requirement of a responsible Government to regulate the digital media. In this direction, the Government wanted to introduce certain “Ethical Code” for the so called “Digital Media” who were “News Intermediaries” and fell under the provisions of Section 79 of ITA 2000.

The Intermediary Guidelines of 2021 therefore had some provisions which included

- Self regulation by a digital media

- Self regulation by an industry group consisting of different members of the digital media

Beyond these two levels of self regulation, the Government had planned to have a administrative mechanism for oversight with a “Compliance Official” at the Ministry level

Such administrative oversight is required as part of Governance and it is surprising that the Courts donot appreciate such governance controls being established particularly to any body who sports a tag of a “Journalist”.

The main objection raised before the Court was therefore that an “Ethical code” was being suggested and such an ethical code would cause a “Chilling Effect” on freedom of expression. Some of the media Moghuls appear to think that they cannot be made accountable even for malicious news reporting and they donot want even a self regulation. “Say No to Ethics” seems to be the slogan of the petitioners.

The division bench of Madras High Court has stayed “by way of abundant caution”, sub rules (1) and (9) of Rule 9 of IT Rules 2021. Earlier the Mumbai High Court had stayed sub rules 9(1) and 9(3).

The High Courts have been liberal in expressing that they are protecting the “Freedom of Press”, and that the rules cause a “Chilling Effect” on freedom of expression and is “Ultra Vires” the ITA 2000. Additionally, new Jurisprudence is being brought in by the Madras High Court stating that the decision of the Mumbai High Court should have a “Pan-India” effect.

In a democracy while the executive has to respect the judiciary, the Judiciary also has to respect the executive and recognize that they have certain duties. Imposing “Ethics” on media cannot be considered as “Manifestly unreasonable” as the Mumbai High Court said in its order.

We can observe that the same courts had a different interpretation of freedom of speech when they were confronted with the rights of Arnab Goswami or S V Shekar. The lack of consistency is perplexing.

Let’s see what Rule 9(1), 9(3) and (9) state which the Courts felt necessary to stay.

-

-

- Observance and adherence to the Code.—

-

(1) A publisher referred to in rule 8 shall observe and adhere to the Code of Ethics laid down in the Appendix annexed to these rules.

(2) Notwithstanding anything contained in these rules, a publisher referred to in rule 8 who contravenes any law for the time being in force, shall also be liable for consequential action as provided in such law which has so been contravened.

(3) For ensuring observance and adherence to the Code of Ethics by publishers operating in the

territory of India, and for addressing the grievances made in relation to publishers under this Part, there shall be a three-tier structure as under—

(a) Level I – Self-regulation by the publishers;

(b) Level II – Self-regulation by the self-regulating bodies of the publishers;

(c) Level III – Oversight mechanism by the Central Government.

Under Rule 8, these guidelines are applicable to publishers of news and current affairs content and publishers of online curated content, provided they operate in the territory of India or such publisher conducts systematic business activity of making content available in India.

The appendix referred to above states

(a) “A publisher shall not transmit or publish or exhibit any content which is prohibited under any law for the time being in force or has been prohibited by any court of competent jurisdiction.

(b) A publisher shall take into consideration the following factors, when deciding to feature or transmit or publish or exhibit any content, after duly considering the implications of any content as falling under the following categories, and shall exercise due caution and discretion in relation to the same, namely:—

(i) content which affects the sovereignty and integrity of India;

(ii) content which threatens, endangers or jeopardises the security of the State;

(iii) content which is detrimental to India’s friendly relations with foreign countries;

(iv) content which is likely to incite violence or disturb the maintenance of public order.

(c) A publisher shall take into consideration India’s multi-racial and multi-religious context and exercise due caution and discretion when featuring the activities, beliefs, practices, or views of any racial or religious group.

Rest of the appendix talks about providing ratings such as U, U/A etc which is commonly used in other context such as film censoring.

It is difficult to understand which part of this rule is considered “Chilling”. It appears from the ruling of the Court that the “Reasonable Exceptions under Article 19(2) of our constitution” is what the Court is referring to as “Causing Chilling Effect”.

If the Court was seriously concerned only about the oversight mechanism, then there would have been no need to stay 9(3)(a) and 9(3)(b) which was creation of the self regulatory systems (supported by the grievance redressal mechanism).

The Court makes a reference to the “Shreya Singhal Case” where the Supreme Court had interpreted the law applicable to “Transmission” of an electronic message (under Section 66A of ITA 2000) to “Publishing” of an electronic message in Twitter and Face Book and struck down the section without taking efforts to read it down.

Similarly in the current case also the Court has resorted to staying rule 9 (1) and 9(1)(3) when it was not necessary.

It appears that Courts themselves need to impose a self regulation on themselves not jump to scrap the law at the drop of the hat. Where necessary they should exercise the option of “Reading down” the law so that the functioning of the Government is not disrupted but the misuse of the law is prevented. If the Courts are trigger happy and shoot down not only the laws but also the administrative notifications, then the executive will stop being decisive. This will encourage inefficiency and procrastination.

In the instant case, “Digital Publishers” cannot escape being recognized as “Intermediaries” under ITA 2000 and hence they have to be accountable for what they publish to the extent of tagging the content, removing the content when there is a Court order etc. This cannot be considered as “Ultra-Vires” ITA 2000. The ethical code itself is within the provisions of Article 19(2) and the earlier Supreme Court decisions and hence the current Court order appears to be challenging Article 19(2) of the Constitution.

When the dust settles down on this case, three questions remain to be answered by the judiciary.

One of the questions is to what extent a decision of a High Court in one state should be considered as applicable “Pan-India”. If this is universally acceptable, there is a possibility that desired decisions adverse to the Government may be obtained by a clever choice of the High Court.

The second question is whether the Courts should resort to striking down administrative guidelines as easily as they seem to do without appreciating the long term impact it may have on converting a functioning executive to a non-functioning executive which will reduce the efficiency of Governance.

The third question is whether the Courts should exercise a self regulation for themselves and use “Reading down Provision” as a rule and not strike down provisions of law. When the striking down is for provisions having direct reference to Article 19(2), it is questionable if such an order itself is ultra-vires the powers of the Court at this level.

Like we say “Bail is the rule and Jail is an exception, “Reading down should be the rule and scrapping of law/staying of the law should be an exception”

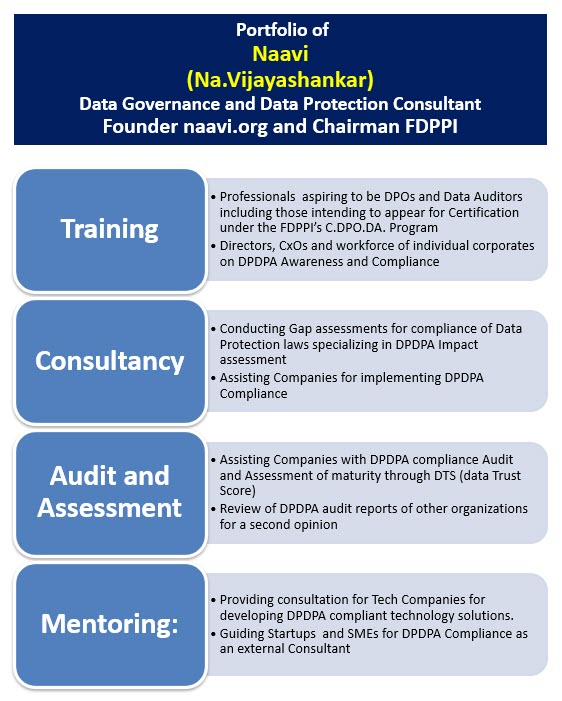

Naavi

Celebrity tweeters and “Fake Journalists” maliciously commented on Indian affairs, often misleading the public. This regulation aims to promote accountability in online platforms, akin to traditional media oversight. Engaging in this discourse feels like playing wordle unlimited, navigating through complex words to find clarity amidst confusion.