Recently a judgements from Hyderabad under ITA 2000/8 has raised interesting debates in Cyber Law Circles which make a good case study for academic purpose.

Presently we are commenting on the basis of the following two news reports

Times of India Report : Navy Man gets 2 years imprisonment

Indian Express Report : Sentence under Section 66A.

We shall try to get the copy of the judgement for further clarification.

One of the debates that has ensued post the judgement is that the conviction includes “Section 66A” which the Supreme Court quashed on 24th March ,2015 , in what is popularly called the Shreya Singhal Case.

Most specialists are shocked at how the Court can pass a sentence on a section which has been termed by the Supreme Court as “Anti Constitutional” and quashed.

Does it indicate that the lower Court was ignorant? Did the investigating officer mislead the Court? are some of the questions that are making rounds.

The facts of the case indicate that the incident happened in 2010. At that time the victim was a minor and Section 66A was still valid. The object of crime was an online Chat dated 27th February 2010 where the accused was supposed to have lured the girl to an online relationship. The conviction is said to be under Sections 67, 67-B, IPC 509 besides Section 66A.

The accused has now preferred to file an appeal and the final word on the judgement will be known later.

As regards the Court giving a judgement against the Supreme Court view, it appears that the Judge has gone with the view that the Shreya Singhal judgement did not have any “Retrospective” effect and the cause of action in the current case arose in 2010 when Section 66A was very much valid. In our opinion, this is a correct reading of the Shreya Singhal judgement and the Judge must be credited for his brave decision against the popular sentiment.

If it is argued that at the time of judgement Section 66A had been scrapped and hence this should have been taken into account by the judge, the case also arises that at this point of time, the victim was no longer a “Minor” and 67B was not applicable, though Section 67 was still applicable.

Further the presentation of admissible evidence should have been done under Section 65B (IEA) certification though this loses significance if the accused admitted the offence.

But the judgement has really raised an important point that we need to look at an offence in the light of the date on which the cause of action arose and the laws present at that time unless there is a compelling law that brings retrospective or prospective effect to the provisions. October 17, 2000 was when Section 67 of ITA 2000 and Section 65B of IEA became effective and October 27, 2009 was the day when Section 67A, 67B, and 66A became effective and March 24 2015 was the day whn Section 66A was quashed. These dates have to be kept in mind by Police and Courts to apply the different provisions of law as contained in ITA 2000.

The second point of debate that has come up in the case is that the accused was a Navy personnel. The victim was the daughter of a Navy personnel and the crime was committed on board a Navy vessel. In this case the question of whether the jurisdiction for trial should have been with the Military Court is a point to discuss. Probably the victim was not on board the Navy vessel and was in the Civil area. (Or was she residing in a Cantonment area?).

Had the Navy Court taken cognizance of the matter and started a trial, it would have been difficult for the Hyderabad Court to proceed with the trial as it would have become a fit case for “Double Jeopardy”. By not initiating action, the Navy has allowed the proceedings in the Hyderabad Court to continue.

I understand that Madras High Court in a case in 2009 had refused to transfer a criminal case to the Army Court. (Refer here). This was however a case of physical crime of murder in the civil society and stood on a different ground. In that case the person was on leave and the claim for transfer was based on Section 475 of Cr Pc which states as under:

Quote:

475. Delivery to commanding officers of persons liable to be tried by Court- martial.

(1) The Central Government may make rules consistent with this Code and the Army Act, 1950 (46 of 1950 ), the Navy Act, 1957 (62 of 1957 ), and the Air Force Act, 1950 (45 of 1950 ), and any other law, relating to the Armed Forces of the Union, for the time being in force, as to cases in which persons subject to military, naval or air force law, or such other law, shall be tried by a Court to which this Code applies or by a Court- martial; and when any person is brought before a Magistrate and charged with an offence for which he is liable to be tried either by a Court to which this Code applies or by a Court- martial, such Magistrate shall have regard to such rules, and shall in proper cases deliver him, together with a statement of the offence of which he is accused, to the commanding officer of the unit to which he belongs, or to the commanding officer of the nearest military, naval or air force station, as the case may be, for the purpose of being tried by a Court- martial. Explanation.- In this section-

(a) ” unit” includes a regiment, corps, ship, detachment, group, battalion or company,

(b) ” Court- martial” includes any tribunal with the powers similar to those of a Court- martial constituted under the relevant law applicable to the Armed Forces of the Union.

(2) Every Magistrate shall, on receiving a written application for that purpose by the commanding officer of any unit or body of soldiers, sailors or airmen stationed or employed at any such place, use his utmost endeavours to apprehend and secure any person accused of such offence.

(3) A High Court may, if it thinks fit, direct that a prisoner detained in any jail situate within the State be brought before a Court- martial for trial or to be examined touching any matter pending before the Court- martial.

Unquote:

According to this section, the Magistrate “Shall” transfer the case to the commanding officer, though the word “in Proper cases” is subject to interpretations. The Madras High Court used this interpretation to refuse transfer of the trial to the Military Court.

However, under the Uniform Code of Military Justice -UCMJ (Refer here) if the offender is an active service member, the UCMJ applies. If the Crime violates both the State Civilian Law and Military law, it may be tried by either or both. But the two Courts need to coordinate and avoid “Double Jeopardy”.

In the Telengana Case, this point was completely missed though this being a “Cyber Crime”, the “Crime is deemed to have been committed at a place from which the offending message was sent, namely the Navy vessel”. Hence the place of crime was a military space and the offender was a military personnel. Even the principle of natural justice indicated that the trial should have proceeded in the military Court since the complainant was also a Navy person (victim being a minor).

Since in the case,

a) Jurisdiction of the Civil Court is itself questionable

b) Evidence was in admissible due to lack of Section 65B certification (assuming that the admission is not sufficient)

the judgement requires a review.

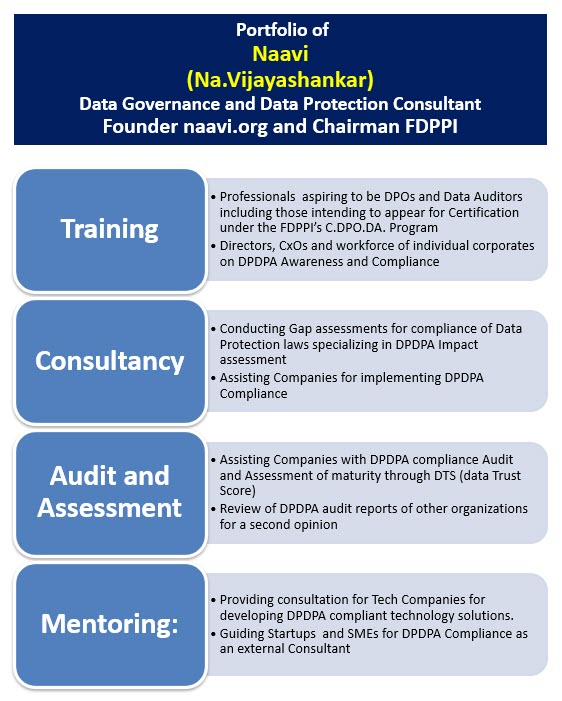

Naavi

(P.S: I am waiting for further information on this case as well as Supreme Court judgements on Section 475 of CrPc based on which supplementary discussions can be continued by experts)

Related Article:

This article says that defence of Double Jeopardy is not available. Needs to be explored further by experts.