(This is in continuation of the earlier article on PDPA 2018)

After the discussions on Aadhaar the other hotly debated aspect of Srikrishna Committee’s report and the draft PDPA 2018 is the “Data Localization” recommendation.

The PDPA 2018 has recommended under Sections 40 and 41, the regulations on cross border movement of data and there is a strong opposition from the industry circles on the proposed requirement that suggests that at least one serving copy of personal data generated in India has to be retained in India.

The Data Localization debate has also triggered the concept of “Data Sovereignty” under which it is argued that the nation has the right to expect control over data that belongs to it.

We can refer to a well articulated opinion expressed in Economic Times today titled ” Data Sovereignty-Economic Implications for the country”

The Indian IT industry represented by NASSCOM which was represented in the Srikrishna Committee as DSCI has through a dissent note submitted as part of the report expressed its reservations on the recommendations of the Committee. The industry is continuing to lobby for a change so that the proposed recommendation is scrapped.

Until there was no specific data protection law in India, the IT industry lobbied for the law stating that it is important under the EU data protection guidelines. The EU guidelines even before GDPR threatened that no data would be transferred to Indian data processing industry unless there is a strong data protection law in India. The industry failed to recognize that ITA 2000/8 was itself a strong data protection law in India and was sufficient to claim the status of a “Adequate Data Protected Nation” under EU regulations. What was lacking was perhaps an effective implementation which could have been corrected administratively without another law.

However, after the Supreme Court jumped into the fray with the Puttaswamy judgement essentially to reign in the use of Aadhaar, there was no option for the Government but to develop a separate Personal Data Protection Law and the result is the PDPA 2018. While the industry was earlier crying that data inflow has been curtailed because of lack of a law in India, now they are raising an objection that the law is restricting the data outflow. The stand taken by the industry therefore lacks conviction and looks like a lobbying by vested interests.

Let’s us first see what PDPA 2018 has proposed and what are the objections of the industry.

Section 40 of the proposed PDPA 2018,

40: Restrictions on Cross Border Transfer of Personal Data

(1) Every data fiduciary shall ensure the storage, on a server or data centre located in India, of at least one serving copy of personal data to which this Act applies.

(2) The Central Government shall notify categories of personal data as critical personal data that shall only be processed in a server or data centre located in India.

(3) Notwithstanding anything contained in sub-section (1), the Central Government may notify certain categories of personal data as exempt from the requirement under sub- section (1) on the grounds of necessity or strategic interests of the State.

(4) Nothing contained in sub-section (3) shall apply to sensitive personal data.

For the purpose of this section, data has to be considered as belonging to four types namely

a) Personal data to which Section 40(1) applies

b) Critical Personal data to which Section 40(2) applies

c) Exempted categories of data to which Section 40(3) applies

d) Sensitive Personal data to which Section 40(4) applies.

Of these, Personal data and Sensitive personal data is defined in the law and the Critical and Exempted data categories need to be notified by the rules or the Data Protection Authority of India (DPAI) when established.

Essentially the restrictions under Section 40 states that “Sensitive Personal Data” has to be compulsorily retained within India. As regards Personal Data, a copy alone need to be compulsorily retained in India and otherwise the data can move freely outside. Additionally the Government has kept the power to notify any other type of data that can be mandated for processing in India as “Critical Information” and those which can be exempted for local retention (of even a copy) under grounds of necessity or strategic State interests.

We should also observe the section carefully and note that Section 40(1) applies only to personal data to which this Act applies.

To understand Section 40(1) we need to therefore visit the definition of Personal Data and the Applicability of PDPA 2018.

The definition of “Personal Data” under Section 3(29) follows the global standards of defining anything and everything as “Personal” and if we raise objection to this, the very foundation of all personal data protection laws including GDPR would be threatened.

The definition given is

“Personal data” means data about or relating to a natural person who is directly or indirectly identifiable, having regard to any characteristic, trait, attribute or any other feature of the identity of such natural person, or any combination of such features, or any combination of such features with any other information”

The definition is clearly omnibus with the use of the words “relating to”, “Indirectly identifiable” and “any combination”.

Data exists for a purpose and Law basically exists for the protection of a “Natural Person”. Hence almost all “Data” is indirectly related to a Natural person. In the days of “artificial Intelligence” supported by “Quantum Computing Power”, it is impossible to find data that is not related a natural person. Take for example a “Google Glass”. If I am wearing a Google Glass, every thing I see around me can be tagged to the identity of the face recognition. A Place can be identified with the people who have visited the place and it becomes “related to an individual”.

To expect any data to be “Not Related to a Natural Person indirectly or directly even with a combination of information sorrounding it and the use of technology” is a figment of imagination and living in a fools paradise.

I therefore consider that the law whether PDPA 2018 or GDPR has to recognize its own limitations and provide for a less than universal definition of “Data to which this Act applies”.

If we donot recognize this, there will be endless litigations and Supreme Court of India will have nothing to do expect interpreting how a particular piece of data is related to an individual.

This article which you are reading on the internet is a non-personal data but it is related to a person whose nick name is Naavi but who has a real name and identity associated with an e-mail address, a mobile number, aadhaar etc. Can we then say that this article is subject to Section 40(1) of PDPA 2018?. A strict interpretation will essentially agree with such an interpretation.

We therefore should recognize that if we donot confine the meaning of the “Personal Data” and remove the word “Indirectly” and stick to specific identifiers being defined (like in HIPAA), we are in for a chaotic time. This is not just for PDPA 2018 but also for all other legislation such as GDPR.

We shall however for the time being donot stir this hornet’s nest and accept the word “Indirect” as part of the definition and move on.

(To Be continued)

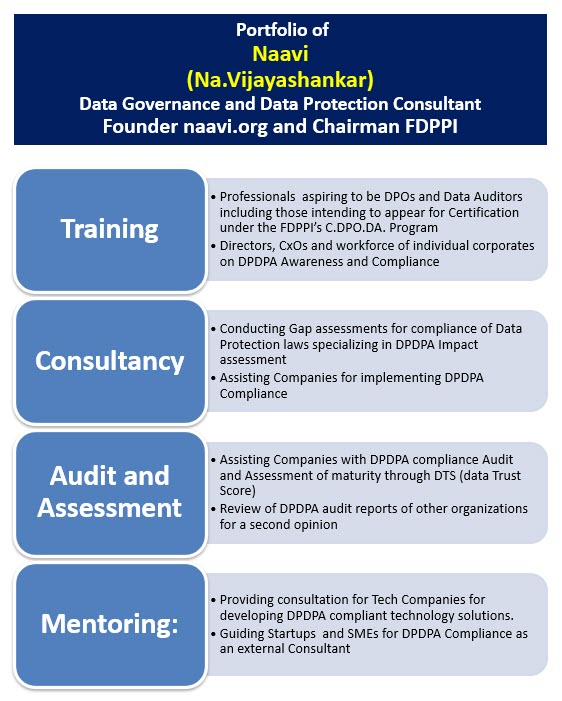

Naavi

Pingback: Personal Data Protection and Data Localization-2 | Naavi.org