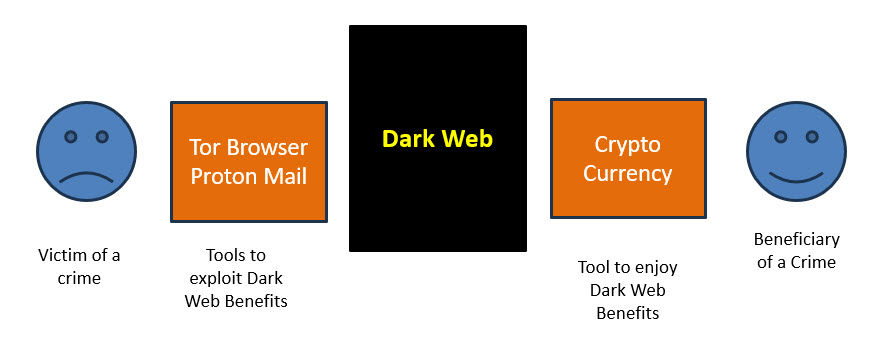

Yesterday we had a very useful discussion on whether there is a need to regulate the Dark Web and whether it is desirable and whether it is feasible.

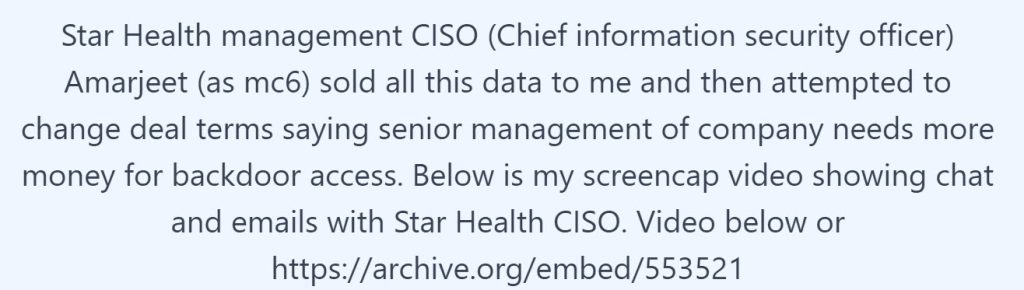

As expected one school of thought was of the firm view that “Dark Web” cannot be regulated and if you try to bring down one Tor Site, another will come up and so on. There are no two opinions that hackers who function in the Dark Web are confident that the law enforcement cannot catch them. There are law enforcement persons as well as security professionals who simply are happy observing the dark web. In fact many security professionals make a living out of monitoring the dark web.

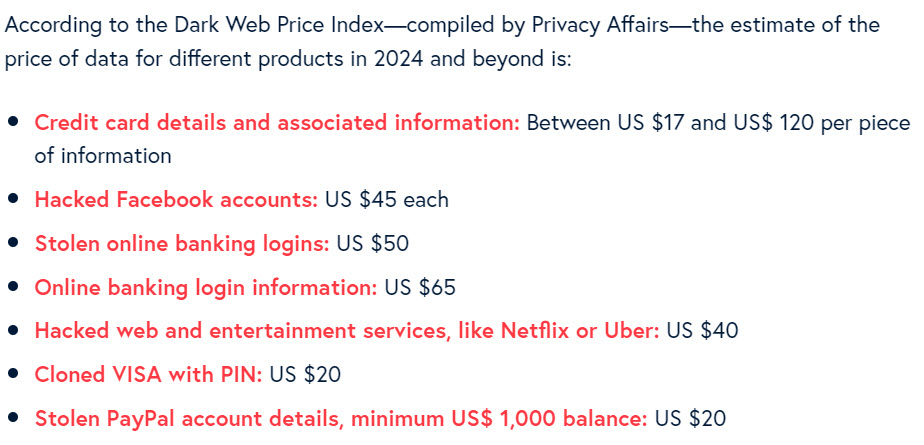

The fact that dark web is thriving because of the presence and availability of crypto currencies like Bitcoins and Monero is well known.

One common view of the professionals was that even politicians are having a cut in cyber crime proceeds and in Crypto Form and hence they are not interested in taking any action against them. It was however noted that regulation of Crypto currencies in India has been effective and Indians are using Dubai as the center for exchange of their black wealth to Crypto currencies and back. Havala operations are also in place between India and Dubai so that ransom money payments demanded in crypto currencies can be carried out.

At the end of the discussions, it was clear that the need for regulation of Dark Web and Crypto Currency is very much needed unless we want a “Digital Jungle Raj” in Digital India.

However there is no consensus on whether any regulation is feasible on Dark Web in India. Many are obviously against such regulation since their lively hood could be affected. They belong to that school of thought that let there be Crimes, Let there be victims of Cyber Crimes. We shall make our money through legitimate business surrounding dark web.

At Naavi.org we believe that “Impossibility of regulating Dark Web” is only an excuse not to try.

In fact we have not prevented road accidents but we have laws for traffic management. We have similarly laws on drug abuse or gun selling or terrorism but we are not able to eliminate them. What we as a society need to do is to take a position to declare that we would not support the Dark Web and the Dark Currency come what may.

It does not matter we shrink our Web space by creating an “Iron Curtain” and restrict use of Internet, ban the domains such as proton mails and continue to ban any substitutes that may come up.

If we cannot ban Tor browser because it is required for any reason, then make it’s possession subject to registration of a person as a “Registered Ethical Hacker” and bring accountability to the use of the Tor browser.

Under Section 67B of ITA 2000, any person who creates text or digital images, collects, seeks, browses, downloads, advertises, promotes, exchanges or distributes material in any electronic form depicting children in obscene or indecent or sexually explicit manner.

A similar law should be considered for restricting the use of Dark Web.

Under Section 84 C of ITA 2000, Whoever attempts to commit an offence punishable by this Act or causes such an offence to be committed is also punishable.

Dark Web which is an instrument of crime along with Tor browser, Proton mail (and other similar services) as well as the Bitcoin type of Private Crypto Currency are all therefore classified as instruments which “Causes such offences…..defined under ITA 2000” . Hence there is already a law that can be used against the use of Criminal Instruments.

Any person in possession of dangerous weapons in the physical world is looked upon as a potential threat to the society and Police maintain a register of such persons as “Rowdie Sheeters”. At the same time we allow police, security agencies and celebrities including people like actor Govinda to possess revolvers for their own safety or for other purposes.

Similarly, we can mandate that any person who wants to use any of the dark web tools should be registered with the national security agency as a “Registered Ethical hacker” and report his activities periodically in the form of an audit report. This will bring accountability to the use of dark web by security persons and segregate them from “Unregistered ethical hackers” who can be classified as “Black hat hackers”.

We advocate MHA to bring in an explanation to the existing laws at appropriate places to state “Possession of dark web tools …as per a list to be published … will require mandatory registration failing which the possession itself will be punishable.

We agree that a section of the society will ignore the law. It does not matter. Let us at least give an opportunity to the “Friends of the digital society” to declare their honesty in good faith by registering themselves as persons who possess ability to wade into criminal space but use it responsibly.

Naavi