The recent spate of fake Bomb threats to different Airline companies and an open advisory from a Khalistani Terrorist not to travel in Air India are acts of terrorism that fit well into the definition of Cyber Terrorism under Section 66F of ITA 2000.

It is surprising that the Ministry of Aviation seems to be searching for ways to strengthen the aviation laws to make such threats punishable. I request the Civil Aviation Minister Ram Mohan Naidu Kinjarapu to take note that there is already a law in India under Section 66F of ITA 2000 which states inter-alia as follows.

“Who ever “with an intention to strike terror in any section of the people”, accesses a computer resource exceeding authorised access and by mens of such conduct is likely to cause disruption of services essential to the life of the community, shall be punishable with life imprisonment”

Hence there is no need for a separate law and tweaking of Airlines Rules to file a case of terrorism against those who send the fake emails either to Airlines or to schools etc with bomb threats. Once such cases are filed, they are recognized across the globe and can be taken to Interpol for investigation if required.

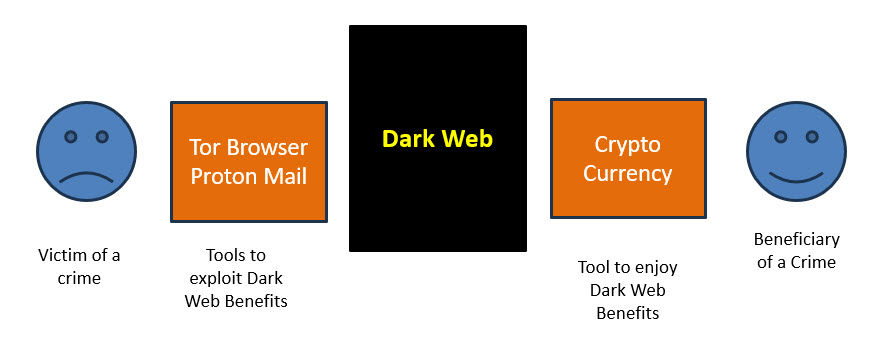

The reason why these threats are proliferating and will continue to proliferate is that it is child’s play to get an email account in Proton Mail or similar email services which provide an anonymous E Mail account from which such threats can be sent. There are proxy servers which provide services to hide the IP addresses also. It is therefore near impossible for the investigating agencies to quickly decypher the identity of the sender.

While it costs almost nothing for the attacker to send an email, it costs in the range of Rs 25 lakhs for airlines to divert flights in mid air for security reasons, conduct a security drill before it is released once again. In view of the ease and economy of such cyber attacks, these will continue and a solution has to be found by the Government as otherwise the asymmetric attack will cause huge damage to the country.

The solution to this lies in getting the cooperation of the service providers like Proton Mail or the VPN service providers to get the identity of those who use the facilities for committing international terrorism. The contracts of such providers always indicate that the services shall not be used for terrorism.

For example the terms of service of Proton Mail indicate as follows:

Any Account found to be committing the listed unauthorized activities will be immediately suspended.

2. Authorized use of the Services

You agree not to use your Account or the Services for any illegal or prohibited activities. Unauthorized activities include, but are not limited to:

- Disrupting the Company’s networks and Servers in your use of the Services;

- Accessing/sharing/downloading/uploading illegal content, including but not limited to Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) or content related to CSAM;

- Infringing upon or violating the intellectual property rights of the Company or a third party;

- Harassing, abusing, insulting, harming, defaming, slandering, disparaging, intimidating or discriminating against someone based on gender, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, race, age, nationality or disability;

- Trading, selling or otherwise transferring the ownership of an Account to a third party (with the exception of Lifetime Accounts, which can be sold or traded exclusively through the Company);

- Promoting illegal activities or providing instructional information to other parties to commit illegal activities;

- Having multiple free Accounts (e.g. creating bulk signups, creating and/or operating a large number of free Accounts for a single organization or individual);

- Paying for your subscription with fraudulent payment means, such as a stolen credit card;

- Engaging in spam activities, which are defined as the practice of sending irrelevant or unsolicited messages or content over the internet, typically to a large number of recipients, notably for the purposes of advertising, phishing, or spreading malware or viruses;

- Sending junk mail, bulk emails, or mailing list emails that contain persons that have not specifically agreed to be included on that list. You agree not to use the Services to store or share content that violates the law or the rights of a third party;

- Abusive registrations of email aliases for third-party services;

- Attempting to access, probe, or connect to computing devices without proper authorization (i.e. any form of unauthorized “hacking”);

- Referring yourself or another one of your accounts to unduly benefit from our referral program’s benefits (see section 9 for discretionary benefits of the program).

Similar conditions will be available in all VPN services as well as all domain name services.

The first requirement for our law enforcement is therefore to quote these terms and demand that the service provider disclose the identity details of the account holder who is committing a terror activity. This can be supported with a Court order.

In case these service providers refuse to abide by the request, it can be escalated into a notice alleging an attempt to shield the perpetrator of the crime and make the service provider a c0-accused for conspiracy. This will provide power for the law enforcement to take direct action against the service provider in an Indian Court and later enforce it in the relevant country in which the service provider is registered. They will not be eligible for protection under Section 79 of ITA 2000 if they donot cooperate with the information sought with a due process of law.

In the meantime, the law enforcement can also take action to block the domain such as “Protonmail.com” from India along with the associated VPN services ignoring the cries of the digital andolan jeevies.

I request the MHA and MeitY to immediately initiate action to co-operate with the Ministry of Civil Aviation in initiating an action in the above direction.

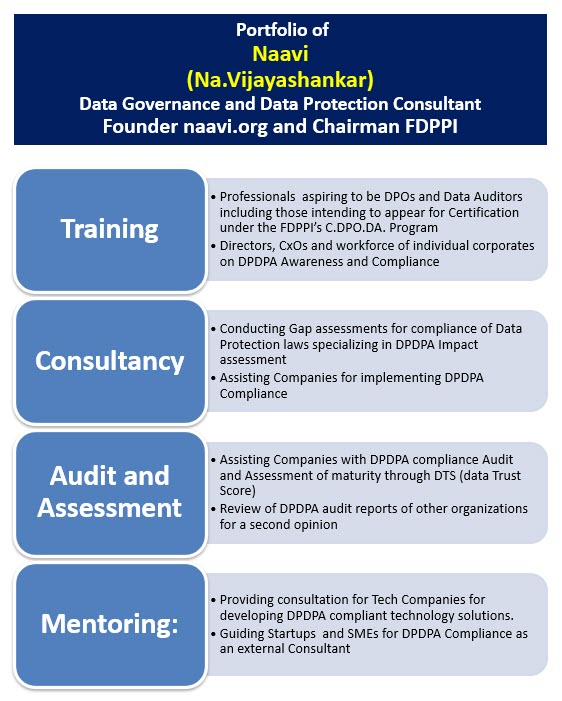

Naavi