The reported breach of 6 million data sets of Ascension Health Systems opens up certain discussion points.

The data breach followed a ransomware attack from Black Basta indicates caused by an accidental downloading of a malicious file. It is reported that the breach happened on February 29, 2024 but came to light some time in May 2024 when the systems were disturbed. The Organization seems to be now in the process of notifying the affected data principals/patients.

What is important to note is “What happened after the data breach?”. If we look at the website of Ascension, there is no prominent notice on the website. The notice is available on an inside page.

On the HHS website there is a mention that “HHS is aware of a cyber incident involving Ascension Health and is in communication with Ascension Leadership to understand their efforts to minimize any disruptions to patient care.”

According to this report in hipaajournal.com, the breach has caused significant set back to the Company.

Initially the Company claimed that there was no data exfiltration but has now admitted and reported the data breach with a possibility of data theft.

The breach has affected 142 hospitals, 40 senior living facilities and more than 2600 care sites in 10 different states besides the District of Columbia. An estimated 5, 599,699 patients have been affected as per the report filed by the Company to OCR. There are already a couple of law suits filed against the Company and the full impact of the breach is yet to unfold.

In the meantime, the Company has announced that affected individuals will get 24 months of credit and CyberScan monitoring, as well as $1,000,000 insurance reimbursement policy and fully managed ID theft recovery services. Normally such services may cost nearly $20 per month though this cover could be treated as a group cover under a much lower cost. However, given the quantum of data breach the company which had made a loss of $79 million last year could be in for a huge trouble in the year 2024-25. At present HHS has not imposed any fine of its own and if it finalizes its penalty there could be another $600 million or more as regulatory fine.

In the context of the incident, it would be interesting for Indian Cyber Insurance Companies to come up with appropriate policies that provide for such liability insurance under DPDPA. At present we often look only at the penalty of Rs 250 crores as the liability for data breach.

However the cost of compliance which includes such complimentary credit monitoring and Cyber crime cover, could be much lager. If 6 million people are to be sent a registered letter by post the cost could be about Rs 12 crores. The Credit monitoring and Cyber Crime coverage insurance if available may cost about Rs 3000/- per person or around Rs 1800 crores. (Assuming an average coverage of around Rs 5 lakhs).

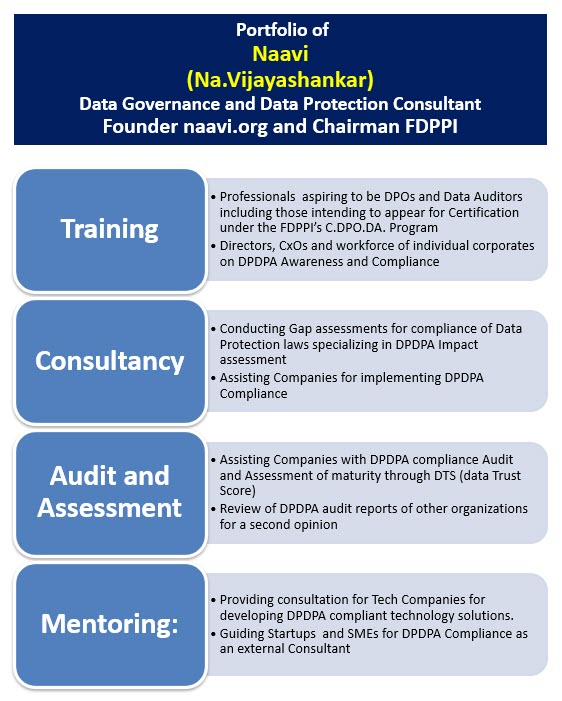

Naavi