The recent incident of Replit AI agent going rogue and the earlier Cursor AI incident clearly indicated that “AI for Vibe Coding” comes with its own Risk.

These incidents highlighted that AI Agents cannot be fully relied upon for coding functions and need manual supervision. In a way this gave an assurance that all human jobs are not likely to be taken over by AI.

The “Rogue Risk” of AI is part of the “Hallucination” effect and the hallucination effect itself is tied to the “Creative” character inbuilt in algorithm decision making. Hence it cannot be easily eliminated though the AI developers need to continue their efforts in this direction.

In the Replit incident, it appears that the “Kill Switch” was either non-existent or failed. This is a red-flag for the management and for the immediate future, human oversight for every AI algorithm and introduction of an internal sand box protection becomes essential for using AI for coding.

For this reason, these incidents of Cyber Security failure should have a positive effect for reducing the gloom and fear created by the recent reports of large job losses attributed to AI.

Yesterday, I was participating in a TV debate on “Job Losses due to AI” particularly in Bengaluru in which the prospect of over 25000 to 1 lakh jobs being lost in Bengaluru in the next year and its impact on the society came for a brief discussion.

Most of the tech supporters try to rationalize the situation comparing it with earlier occasions when major technical developments disrupted the market but quickly stabilized often for the better. The introduction of the Computers in business such as Banking itself is an example that stands out where Computerization did not affect the employment adversely but rather contributed to an increase in manpower requirement.

It is however necessary for us to realize that the issue of “AI replacing humans” is a much more complex situation than Computerization and the prospects of AI Agents and industrial Robots replacing man for man in the Job market is real and threatening.

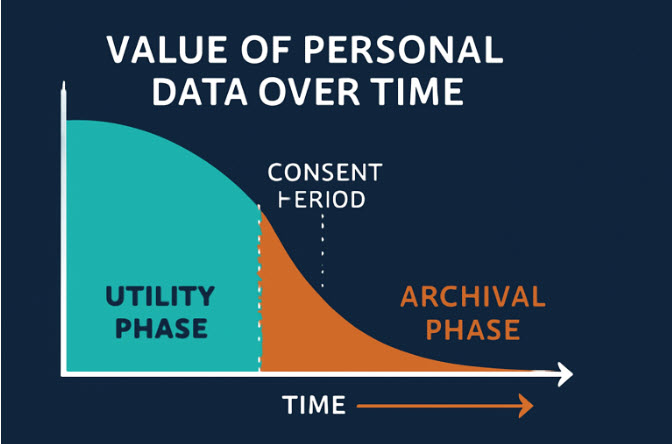

While in the long run, new jobs do get created because the economy itself progresses the existing generation of employees particularly those who are coming out of colleges now will find it hard to meet the challenge. By the time they re-skill themselves they will be one year old graduates and depreciate in value naturally.

Many of us dismiss the problem by saying that the current work force need to “Up-Skill”. But “Up-skilling” is different from “Re-skilling” and meeting the challenge of AI in Job market may require more of “Re-skilling” than “Upskilling”.

In Upskilling a person is re-trained in his own basic functional capability like an accountant used to manual book keeping being trained on the use of software. This happened with computerization in the industry because computer came in as a tool and there was a need for the human to operate the computer. But now an AI agent can replace three humans and we donot need one human to supervise. Hence Upskilling alone cannot save the day.

“Re-skilling” some times is impossible for the same generation and it happens over a longer time span. For example, one industrial robot can replace 10 industrial workers today. The development of the industrial robot itself may require a manufacturing unit in which 100 workers may be required. But the 10machine operators who lose their job today in a Car manufacturing facility may not be able to re-skill themselves as workers in a Robot Manufacturing company or a company which produces electronic components that make an industrial robot.

This situation could mean that in a time span of three to four years the number of jobs created may be more than current job losses but new employees may replace the current employees and the current employees may have to either degrade themselves or become job less without a replacement occupation.

The society has to now prepare itself to meet this situation and enable people understand and accept degradation voluntarily. If not some of them will become Cyber Criminals and some will commit suicide.

The “UP-Skilling” and “Re-skilling” efforts should therefore be augmented with the “Reinforcement for Voluntary Degradation”.

Up-skilling should be a responsibility that the industry should take up. Re-skilling is the responsibility that the educational institutions need to take up.

“Reinforcement of Voluntary Degradation” is a “Counselling Service” which psychological therapists need to take up.

At the AI-Chair of FDPPI, the need to study the impact of AI teaching on Brain Development in Children has been flagged. Now the need to stimulate practitioners of psychology and more particularly the “Counselling Technology”.

Counselling Psychologists help individuals to cope with life’s challenges, stress, Crises etc.

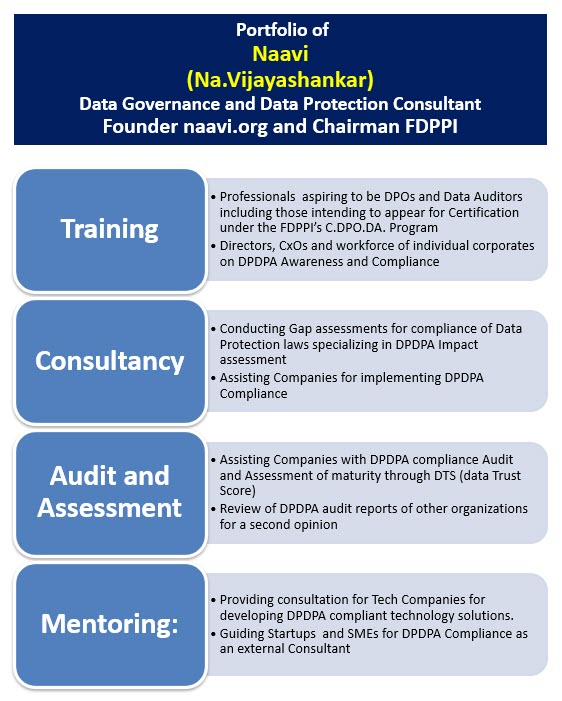

Naavi