When countries move from a “No Data Protection Law” to a “Strict Data Protection Law”, one of the problems faced by the companies is how to handle the legacy personal data which is already with them.

This data could have been collected earlier either without proper consent or without the consent information being available for reference now. Even if the consent had been obtained earlier, it is unlikely that the information provided to the data principal would not have been made as required under the current data protection requirement.

For example, the PDPA of India when implemented would require the notice for personal data collection to include the following points

(a) the purposes for which the personal data is to be processed;

(b) the nature and categories of personal data being collected;

(c) the identity and contact details of the data fiduciary and the contact details of the data protection officer, if applicable;

(d) the right of the data principal to withdraw his consent, and the procedure for such withdrawal, if the personal data is intended to be processed on the basis of consent;

(e) the basis for such processing, and the consequences of the failure to provide such personal data, if the processing of the personal data is based on the grounds specified in sections 12 to 14;

( f ) the source of such collection, if the personal data is not collected from the data principal;

(g) the individuals or entities including other data fiduciaries or data processors, with whom such personal data may be shared, if applicable;

(h) information regarding any cross-border transfer of the personal data that the data fiduciary intends to carry out, if applicable;

(i) the period for which the personal data shall be retained in terms of section 9 or where such period is not known, the criteria for determining such period;

( j) the existence of and procedure for the exercise of rights mentioned in Chapter V and any related contact details for the same;

(k) the procedure for grievance redressal under section 32;

(l) the existence of a right to file complaints to the Authority;

(m) where applicable, any rating in the form of a data trust score that may be assigned to the data fiduciary under sub-section (5) of section 29; and

(n) any other information as may be specified by the regulations.

In the current regulation which was contained under Section 43A of ITA 2000/8, the Reasonable Security Practice rule no 5(3) stated

(3) While collecting information directly from the person concerned, the body

corporate or any person on its behalf snail take such steps as are, in the

circumstances, reasonable to ensure that the person concerned is having the

knowledge of —

(a) the fact that the information is being collected;

(b) the purpose for which the information is being collected;

(c) the intended recipients of the information; and

(d) the name and address of —

(i) the agency that is collecting the information; and

(ii) the agency that will retain the information.

Additional requirements were provided on minimal retention, purpose limitation, right to access and correction, Opt out option, right to withdraw consent, grievance redressal, disclosure norms, security safeguards etc were to be followed by body corporates collecting sensitive personal information, but were not mandated clearly to be part of the “Privacy Policy” to be published which was the “Notice” as we now refer to.

The privacy policy was required to indicate the type of personal or sensitive personal data or information collected, purpose of collection, usage of such information, disclosure and reasonable security.

As we can see though the intention of Section 43A was similar to the PDPA 2020, the details specified as the requirements of notice in the PDPA 2020 are far more than what was envisaged under Section 43A of ITA 2000.

It can safely be said that the consents if any in the pre-PDPA 2020 time would be insufficient to meet the requirements of PDPA 2020.

The Data Fiduciaries therefore have to obtain fresh consents by serving fresh notices to the Data Principals.

In the ITA 2000, there was no concept of a Data Fiduciary and the Data Processor though in the clarifications provided by the Government, it was indicated that the Data Processor was not responsible for the consent and only that body corporate which had a direct relationship with the data subject would be required to collect the consent.

If therefore we strictly interpret the emerging regulations, all legacy personal data with the Body Corporates will have to be forensically deleted as soon as the PDPA 2020 comes into effect or new consents should be obtained.

Assuming that the organisations would send out e-mail notifications to the data subjects and seek the consent based on a new consent, it can safely be assumed that a very large number of such data subjects would either not respond or their e-mail addresses would be no longer correct and hence they would not be able to respond.

In such cases a large number of data sets have to be purged.

When GDPR came into effect, similar problems were faced by the Data Controllers and while most of them might have purged the data, some have archieved them under legitimate interest claims and some might have not taken any action other than sending a reminder for re-permission.

There were many instances where data subjects retorted back to the re-permission request with a question, “Where and when you got my personal information? How are you processing it?, Where is the past consent? etc”.. Unable to face such questions, some companies simply purged the data without making an attempt to renew the earlier consent though this resulted in loss of earlier investment.

In the case of GDPR, since the EU Directive was already in force, perhaps it was not necessary to provide for any transition option from the legacy system to the GDPR system. But in India where the earlier system did not require the consent of the type now required, it would be unfair to penalize those organizations which were in compliance of Section 43A but may fail the current requirements.

Hence there is a need for providing a smooth transition from Section 43A (ITA 2008) based personal data collection to the Section 7 (PDPA 2020).

Such a transition has to provide relief to those organizations

a) Who hold consents as per Section 43A of ITA 2008

b) Send out Opt-In request to the new consent forms but not receive confirmation

to phase out such data over a period of time relevant in the context of the legitimate interest of the organization.

Though it would have been good if this had been covered under a clause to enable the DPA to enable a smooth transition from ITA 2000/8 to PDPA 2020, there is no reason to despair since it is possible that this provision can be covered under Section 14 by the DPA with appropriate notification.

Hopefully if this comes for discussion during the discussions of the JPC and the vested interests who want to delay the passage of the Bill hold it out as one of the reasons why the Bill should be re-considered, the Government would be able to provide an effective counter argument that it could be covered under the notifications from the DPA.

Alternatively a simple additional provision can be added to Section 14 under “Processing of personal data for other reasonable purposes” to include a provision to the following effect.

Section 14 (4) : Where the Authority considers it necessary and expedient, it may through appropriate notification provide for necessary transition from the legacy laws to the provisions under this Act, through the legitimate interest declared in the “Privacy by design policy” as per section 22 of the Act.

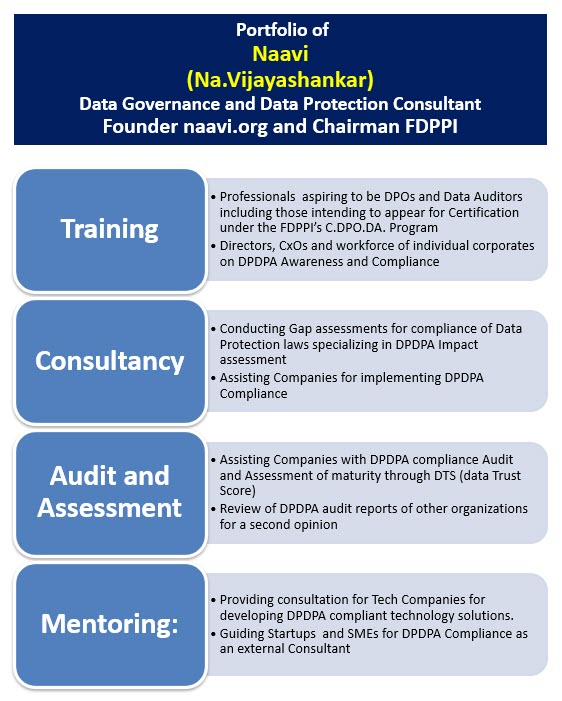

Naavi