[This is a continuation of our earlier article on the Kerala Judgement on Right to Forget]

The Judgment of Kerala Hight Court of 22nd December 2022 in the WP (C) nos 26500/2020 & connected cases was mainly considering the issue of “Right to Forget” and whether it is to be recognized by removal of the identity of parties from published judgements in different contexts.

The Court considered the issue from four different aspects namely Privacy, Courts as democratic institutions, Open Data and Public Interest.

Definition of Privacy

The Court took the Definition of Privacy as a Right as the starting point for the debate on Right to be forgotten and has recorded its views. In the process, the judgement has traced the evolution of the definition of Privacy and contributed to the discussion of the “Theory of Privacy”, which is a concept of exploratory interest for us.

The judgement traces the development of Privacy thus:

“In very early times, the law gave a remedy only for physical interference with life and property, for trespasses vi et armis. Then the “right to life” served only to protect the subject from battery in its various forms; liberty meant freedom from actual restraint; and the right to property secured to the individual his lands and his cattle.

Later, there came a recognition of man’s spiritual nature, of his feelings and his intellect.

Gradually the scope of these legal rights broadened; and now the right to life has come to mean the right to enjoy life,-the right to be let alone; the right to liberty secures the exercise of extensive civil privileges; and the term “property” has grown to comprise every form of possession-intangible, as well as tangible. “

In the process of this development it was recognised that writings or opinions of an individual though not in reality his private property, was considered as an inviolate personality.

The evolution of the definition of privacy then inevitably moves into the domain of technology and the special issues that the virtual space has created as if the definition of privacy is inseparable from the Technology space. It is recognized that Virtual Space has made identity of the individual digitally immortal and Digital immortality defines the continuation of an active or passive digital presence even after death.

As a result new issues of Right to Privacy has arisen and the social and ethical problems in relation to digital immorality and artificial intelligence which can identify the data stored through algorithms are the subject matter of debate of Privacy.

The current problem of “Right to Forget” is traced to this development where there is an intersection of privacy and technology which has become a challenge for the judicial administrator.

It is through this “Digital Immortality” argument (which is a combination of data storage, capability of being indexed, searched and retrieved easily) that the “Right to Forget” discussion has been linked to “Information Privacy” in this judgement. Hence this discussion may be considered as part of the ratio decidendi and not only orbiter dicta as far as this case is considered.

The Court recognized that there are different dimensions of the information before Courts which play an integral role in encouraging fair and transparent decision making by the Courts, giving them legitimacy and contributing to the dissemination of information about the judicial process among the public.

The judgement also makes an interesting reference to the part of the Puttaswamy judgement where a distinction is sought to be made between “Privacy” and “Anonymity”.

According to Justice Chandrachud, “Privacy involves hiding information whereas anonymity involves hiding what makes it personal”.

The Kerala Judgement points out that Privacy is about choice and this choice is sought to be extended as anonymity in court proceedings. It also underscores that “Privacy in the judicial information context is essentially related to the contents of the information in the case. Anonymity on the other hand, in the judicial information sphere, is a process of denying information to the public about the identity of the parties related to a case”.

The Court went on to add…

“Undoubtedly, we have to hold that personal information as above, of the parties in a case, has to be classified as data forming part of his or her privacy. The individual’s right to exercise control over his personal data and to be able to control his/her own life has been recognized in Justice K.S.Puttaswamy’s case (supra) in the separate judgment authored by Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul without recognizing it as an absolute right…..

The existence of such a right does not imply that a criminal can obliterate his past, but that there are variant degrees of mistakes, small and big and it cannot be said that a person should be profiled to the nth extent for all and sundry to know.

The interplay of providing information about the parties and providing information on the contents of the cause in a Court of law requires a balancing exercise. It is exactly that exercise that has to be considered by this Court in these writ petitions in the absence of any legislation.

No one has any grievance against the open, transparent court proceedings and the conduct of cases in the open justice system. The problem for them is allowing their personal and private information to remain permanently in the digital public space, invading their right to privacy and right to forget the past. The task for us, therefore, is to decide not only on the privacy claimed in the present but also in the future.”

The Learnings to be taken note of

Thus it can be observed that the Court has flagged the “Data Storage and Data Retrieval” as the Privacy Risks than the data itself.

It is this aspect that we need to consider the “Right to Erase” and “Right to Forget” as two different concepts in DPDPB 2022. When data is made retrievable by public which is essentially related to “Disclosure” of personal data, the need for recognizing the risk of unfair privacy risk arises.

At the same time, ” Right to Forget” cannot be considered as the “Right to become anonymous” and hence it is to be considered as a limited right to prevent free disclosures.

“Right to Erase” on the other hand is related to the purpose oriented collection and use principle and requires that once the purpose is completed, the personal information should be stopped from being processed. This does not mean that the data has to be “Anonymized” or “Purged irretrievably”.

The Data Fiduciary can retain the purpose-expired data and such data can be retrieved and disclosed in certain circumstances such as there is a request for legitimate purpose.

When data has been archived as purpose-expired, it is debatable if the “Disclosure” needs to be blocked automatically for search and retrieval since there may be a public interest in the information with or without identity.

If however “Right to forget” is recognized and the data principal has placed his “request for right to forget”, then it may be appropriate to block automated disclosure.

Even in such cases, since “Right to Forget” is not “Right to Anonymity”, it may be in order to exempt the restriction to the disclosure to law enforcement agencies or on orders of Court or in Public interest.

This alters the fundamental nature of our understanding of the “Right to Forget” and we have to thank the Kerala Judgement for this clarification.

The principle this establishes is “Right to Forget is not Right to anonymity and the identity can be archived securely in the public interest”.

For example, even when a Court redacts the names of the parties from the copy of the judgement which is published in a data store which is available for Google or Indiakanoon.com to index, within the records of the Court, the Registrar should be able to recognize the parties if required. If the Data Custodian identifies any “Public Interest” in making a voluntary disclosure of the information, there may be fiduciary duty for him to recognize and act accordingly.

For example even in a matrimonial case if the names of parties are held confidential and if there is an instance where one of the parties is a habitual offender and other similar disputes arise indicating the possibility of a criminal intention, then the data custodian may have to consider release of the data to public… may be with the permission of a Court.

Similarly in the Private Sector, if the personal data is held confidential and an incident comes to the knowledge of the company in the public space where there is a link to the data then there may be fiduciary duty for the data fiduciary to voluntarily submit the data to the relevant authorities even though they are at that time classified as “Archived under Right to Forget Request”.

This disclosure of purpose-expired or Right to forget data in the case of deceased data principals where there may be a legitimate interest of the legal heirs (where there is no nomination) needs to be specifically addressed. Also whether Right to forget data is part of the nominee’s right also remains in need of further debate.

(These views of Naavi are subject to challenge and debate)

(… to be continued)

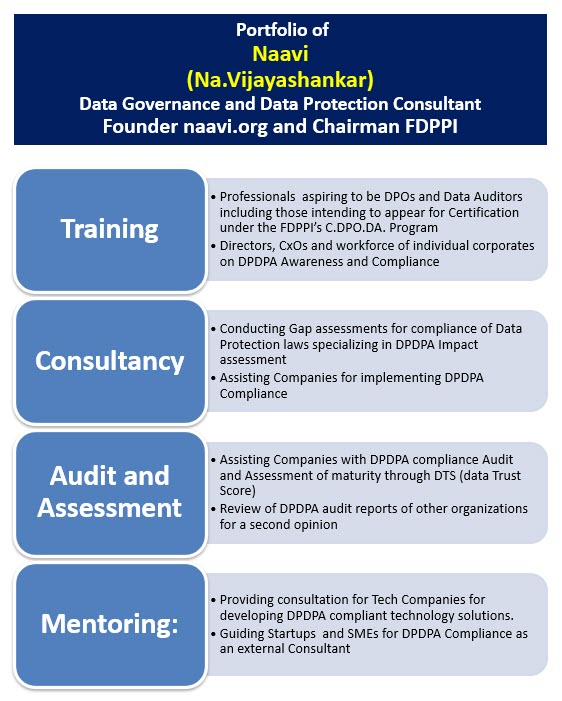

Naavi

All articles in the series:

Hats off to the Kerala Judgement on Right to Forget-5: Evolution of the Right to be forgotten

Hats off to the Kerala Judgement on Right to Forget-4: Need for Transparency in Judiciary

Hats off to the Kerala Judgement on Right to Forget-3: Right to Forget is not Right to Anonymity..

Hats off to the Kerala Judgement on Right to Forget..2: Ratio Decidendi in Puttaswamy Judgement

Hats off to Kerala High Court for it’s treatise on Right to Forget