When GDPR came into effect on 25th May 2018, the most notable aspect of GDPR was the level of penalties for non compliance which could be as high as 4% of the global turnover of a company or Euro 20 million whichever is higher. This was the single most aspect of the regulation which shook up the industry all over the world including in India.

Now that one year has passed since GDPR became effective, we can review how this high penalty regime has worked in practice.

As per a report published at the end of February, it is found that, in the first nine months, there were 206,326 cases reported under the new law from the supervisory authorities in the 31 countries in the European Economic Area. (Refer Report). The total fines imposed amounted to Euro 56 million.

About 65,000 were initiated on the basis of a data breach report by a data controller, while about 95,000 were complaints. Some 52 per cent of the overall cases have already been closed, with 1 per cent facing a challenge in national courts.There were some GDPR cases in progress, but that the past year had been mostly focused on legacy investigations, with fines handed to Uber, Facebook and Equifax. It may be noted that not all the fines were about data breaches. About half of the complaints related to the way subject access requests have been handled.

A list of penalties imposed by different Supervisory authorities is available here.

During the last one year, German data protection authorities have issued 41 GDPR-related fines. Fines were levied for a variety of GDPR violations, such as inadequate technical and organizational security measures, non-compliance with information duties and sending unauthorized marketing e-mails.

Google was fined from France’s data regulator, citing a lack of transparency and consent in advertising personalization, including a pre-checked option to personalize ads.

In Denmark, a Taxi Company Taxa 4X35 was fined 12 M DKK because during a random audit, the company was found to have over 9M personal records the company had stored but did not need to and had failed to delete.

In the UK, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has dished out numerous six-figure fines but none have yet exceeded the £500,000 maximum penalty that was the maximum under the Data Protection Act 1998. The ICO slapped Facebook with the maximum possible fine of £500,000 for the social network’s role in the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

The Polish privacy regulator issued its first GDPR fine, penalizing an unnamed firm over £187,000 for scraping public data on individuals and reusing it commercially without notifying them.

It appears that during this year perhaps many more of the complaints may be further followed up.

It remains to be seen if the fines would result in better compliance in the coming years.

One view in the industry is that despite the media coverage on huge fines, the big companies seem to have actually grown their business in the post GDPR era while the smaller companies unable to manage the cost of compliance have lost their market share.

The counter productivity of high penalty regime has been identified even by HHS for HIPAA implementation which has recently reduced some penalty aspects under HIPAA-HITECH Act.

This is an important observation that we in India need to keep in mind when we implement PDPA in India. The draft E Commerce policy issued by the Government in February 2019 had indicated that small companies need to benefit from the policy and even suggested that MNCs need to share data in public interest with Indian companies.

The DPA should keep this public good objective in mind and ensure that the high levels of fine and the criminal penalties under PDPA are not applied indiscriminately on SMEs.

For this purpose, it may be proposed in the Bill that a differential rate of penalty may be applicable based on the nature of the organization and more specifically if it is incorporated in India and owned and managed by Indian entrepreneurs.

The objective of the data protection legislation is not to enable the DPA or the Supervisory authorities to make undue profits out of the fines but to be able to make the industry take the regulation a little more seriously than they would otherwise take. I suppose this would not be lost sight of when the Indian PDPA is taken up for passing int he Parliament as an Act.

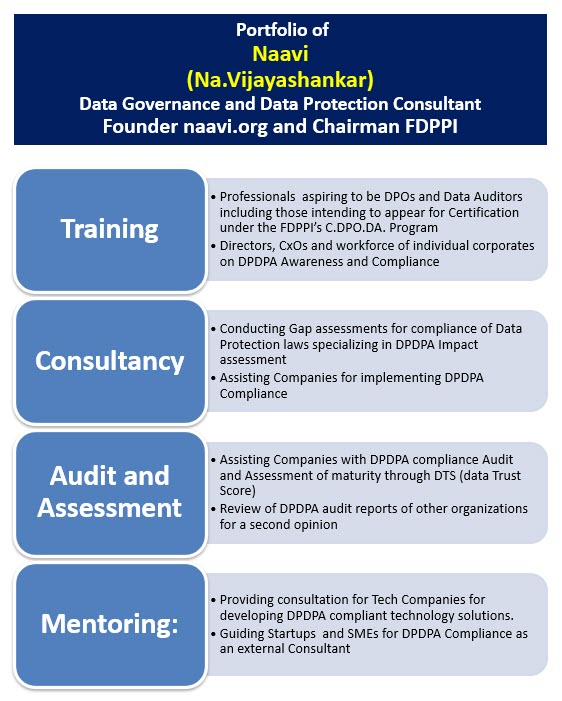

Naavi