One of the key provisions of DPDPA is the introduction of the concept of a “Consent Manager” who could represent the data principal for a better protection of his privacy.

According to Section 6 of DPDPA 2023,

The Data Principal may give, manage, review or withdraw her consent to the Data Fiduciary through a Consent Manager, shall be accountable to the Data Principal and shall act on her behalf in such manner and subject to such obligations as may be prescribed and every Consent Manager shall be registered with the Board in such manner and subject to such technical, operational, financial and other conditions as may be prescribed.

Accordingly, the DPDPA Rules address the requirements of how a Consent Manager may be registered under DPDPA 2023 and what are his functional requirements. Since there is already a term “Consent Manager” under the DEPA architecture proposed by MeitY in another context and used in the Account Aggregator scheme of RBI, we need to distinguish that Consent Manager as “CM-DEPA” and refer to the Consent Manager under DPPDA 2023 as “CM-DPDPA” or simply the “CM”.

Naavi.org has been, since the days when PDPB 2019 introduced the term “Consent Manager” has been consistently projecting it as a very innovative thought. The introduction of a specialist as a Consent Manager who could act as an expert to decipher the request for permissions and assisting the data principal was a master stroke which could enable overcoming of the multiple issues such as “Consent Fatigue”. “Lack of Privacy Appreciation in the society”, “Language barriers”, as well as the difficulty in deciphering the permissions to overcome dark pattern or misleading notices.

We donot know if this was just a follow up of the DEPA Framework or a deliberately introduced feature that could make the Indian law stand out in the world as an innovative legislation. It could have been an accident but a beneficial accident that the concept was introduced in Section 21 of PDPB 2019 stating

“The data principal, for exercising any right under this Chapter, except the right under section 20,(ed: Right to be forgotten) shall make a request in writing to the data fiduciary either directly or through a consent manager with the necessary information as regard to his identity, and the data fiduciary shall acknowledge the receipt of such request within such period as may be specified by regulations”.

“The data principal may give or withdraw his consent to the data fiduciary through a consent manager.” and , a “consent manager” is a data fiduciary which enables a data principal to gain, withdraw, review and manage his consent through an accessible, transparent and interoperable platform. (Section 23 of PDPB 2019).”

The same provisions prevailed in the Data Protection Bill 2021 and are now reflected in DPDPA 2023.

The interpretation provided by Naavi.org that CM-DPDPA is different from CM-DEPA and is having better utility than merely being a software platform was therefore a tribute to the innovative thought of some body in MeitY who drafted the PDPB 2019 whether they had similar intentions or otherwise.

The Rules now under discussion seems to have however ignored the potential of “Consent Manager” as a special kind of data fiduciary who could act as a “Power of Attorney Holder” of a Data Principal or a Trustee of his/her personal data. The rules have relegated the role of CM as a “Software Platform”. This is a classic case of a diamond in the hand being thrown away as just another piece of black charcoal.

The Rule 5 of the draft rule that we now have for discussion that indicates the present thinking of Meity (Check https://www.dpdpa.in/dpdpa_rules/) suggests inter-alia the following provisions which we feel requires a re-look

1. Not specifying that the definition of a foreign company should go beyond mere “Constitution outside India”

2. Stating that every consent manager shall establish …a platform that enables a data principal to give, manage, review and withdraw her consent to herself obtain her personal data from a data fiduciary or to ensure that such personal details shared with another data fiduciary of her choice, without the consent manager being in a position to access that personal data

3. Specifying that the Consent Manager shall not sub-contract or assign the performance of any of its obligations as a consent manager

4. Specifying that the Board may suspend or cancel the registration without specifying how the interests of the data principals are protected.

5. Not specifying prohibition of data transfer outside India.

For the reasons specified below we request the MeitY to reconsider these provisions.

Consent Manager under DPDPA and DEPA

It is recommended that the definition of Consent Manager under DPPDA 2023 should be distinguished from the definition of Consent Manager under the Account aggregator scheme.

At present MeitY seems to be constrained by its own DEPA architecture where Consent Manager (CM-DEPA) was a technology platform and meant for the limited purpose of data users like portfolio managers etc requesting for consent for financial management purpose and such requests were forwarded to data givers like Banks who could provide the information. This served the purpose of relieving the service user from filling up long forms including assets and liabilities, KYC information etc besides demographic information. RBI applied this system in the account aggregator scheme. These use cases are a single purpose usage and not meant for repeated use.

The Consents under DPDPA 2023 are for multiple purposes, required repeatedly for different sets of data elements by different types of data fiduciaries. It includes the financial service providers such as account aggregators as well as Amazon or Zomato type of data fiduciaries who may require one set of data for clearance of payments and another limited set for logistics management etc.

The CM-DEPA system envisages that every consent request is received from a data fiduciary to the data principal during the subscription of a service is referred to the consent manager who again refers it to the data principal, receives the consent and then communicate the information to the data fiduciary. What data has to be shared remains the decision of the data principal and he is required to look through the permission request understand the permission requirement and then approve. For every purchase from Amazon and for every order of food from Zomato, separate notice and consent is required and this process of referring to the CM-DEPA needs to be followed.

In the ordinary course, a data principal goes to a data fiduciary service site and receives the notice which he may click for acceptance. The data goes directly from the data principal to data fiduciary as part of the order.

In the CM-DEPA scheme, there is also a necessity for the CM-DEPA to check the identity of the Data Principal whose request is coming from a third party.

In this process the CM-DEPA does not have any visibility of the data and as long as the platform is suitably configured, data flows in and out like an ISP. It is therefore an “Intermediary” under ITA 2000.

The CM-DPDPA was not conceived to be the replica of this CM-DEPA since it was necessary to address problems such as the Consent Fatigue, the Language barrier and technology understanding barrier in providing consent.

The CM-DPDPA was therefore considered as a person who can represent the data principal with the data fiduciary for not only providing the consent on demand but also for withdrawal of consent or raising any grievance. Hence CM-DPDPA was conceived as a “Trustee of the Data Principal” and not as a simple ISP type intermediary.

CM-DPDPA could therefore have visibility to personal data, he could filter the data for delivery to a particular purpose and challenge the permissions with his superior technical and language capability to avoid dark patterns or misleading permission requests. He could use anonymization and pseudonymisation if required and deliver only such data as is required for a purpose.

For example, amazon order placement team would get the financial information which is normally shared with the payment gateway but may not obtain the demographic or locational data (unless they justify the requirement for appropriate reasons). The amazon or Zomato delivery team would only get the information about the delivery address and not the other details which they can share it with any logistic company. This serves the purpose wise data minimization requirement.

In such a system, the data principal is relieved of the need to check the permissions and understand and be satisfied that a particular data element requested is reasonably required for the purpose or not.

If the concept of CM-DPDPA is merged with CM-DEPA, this advantage would be given up.

The Consent Manager provision in DPDPA 2023 was innovative and like the “Copyright Society” in Copyright law could be considered as an instrument through which Privacy Culture can be built up in the Country and data principals could be helped in protecting their privacy against business which is driven by their profit motive.

We feel that this great opportunity should not be missed. Hence a review of Section 5 as suggested.

Even this system requires the “Fit and Proper Criteria” and hence many of the current provisions are relevant.

However Rule 3(a) needs to be modified to remove the words “Without the consent manager being in a position to access the personal data”

In as much as every “Significant Data Fiduciary” is allowed to sub-contract their work with responsibility, the need to prevent “Consent Manager” from sub-contracting can be reviewed.

On the other hand, it may be specified that every Data Processor of a Consent Manager would be deemed to be a Significant Data Fiduciary himself.

It shall be made mandatory that when a Consent Manager needs to exit or is suspended or services cancelled, the service shall be ported to another licensed Consent Manager so that the data principal is not inconvenienced. Alternatively a time of upto 1 year should be provided for the data principals to switchover to another consent manager of his choice.

The rules prescribe that CM-DPPDA shall be a company but not a “Foreign Company”.

P.S: As per Companies Act

(42) ―foreign company means any company or body corporate incorporated outside India which— (a) has a place of business in India whether by itself or through an agent, physically or through electronic mode; and (b) conducts any business activity in India in any other manner.

This definition is restricted to “Incorporation outside India” and is not sufficient to prevent data laundering. “Data” is a sovereign asset and it has to be protected from being stolen or surreptitiously laundered. Hence the definition of “Foreign Company” should be expanded to include any foreign or non resident share holding that exceeds 10% or controlling interest that exceeds 33% of the members of the Board.

If the Consent Manager is only a platform and every consent has to be approved by the Data Principal, the very purpose of the consent manager to relieve the consent fatigue and difficulty in understanding the permission requirements is defeated. The CM should therefore be more like a “Power of attorney holder” who can take some decisions on his own without disturbing the data principal.

It is also suggested that the rules should prescribe that Consent manager shall not store personal data abroad.

We request the MeitY to consider this suggestion before they release the final version of the draft.

We also request professionals to comment on the above.

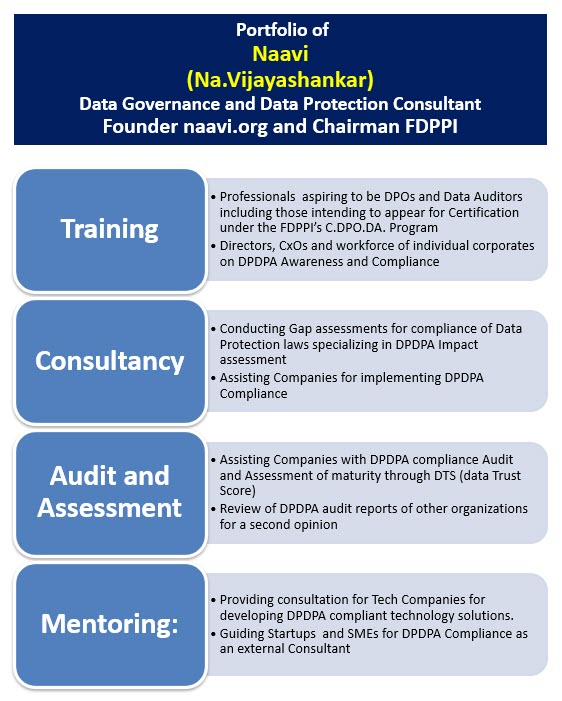

Naavi